(English coming soon)

L’arte religiosa nei musei italiani rappresenta un patrimonio inestimabile che riflette la profonda spiritualità e la storia culturale del Paese. Opere di maestri come Michelangelo, Caravaggio e Giotto adornano le gallerie, testimoniando secoli di devozione e innovazione artistica. Le sculture, i dipinti e gli affreschi raccontano storie bibliche, santi e tradizioni locali, immersi in un contesto di bellezza e contemplazione. I musei, come gli Uffizi a Firenze o i Musei Vaticani a Roma, custodiscono queste opere con cura, permettendo ai visitatori di esplorare il legame tra arte e fede, unendo il sacro alla contemplazione estetica.

L’arte italiana è ricca di opere legate ai temi della Pasqua, che riflettono i momenti cruciali della narrazione cristiana. Queste dodici famose opere d’arte italiane legate alla Pasqua evidenziano il significato teologico e artistico della Pasqua nel contesto del Rinascimento e del Barocco italiano, offrendo una profonda riflessione sui temi della resurrezione, della salvezza e della speranza.

La Resurrezione di Giotto – La Cappella degli Scrovegni, Padova (ca. 1303)

raffigurante Cristo risorto, è parte integrante della storia della Pasqua.

La Resurrezione di Giotto, affrescata nella Cappella degli Scrovegni a Padova, è un’opera straordinaria che testimonia la maestria dell’artista. Situata nella parte alta dell’abside, rappresenta Cristo che emerge trionfante dal sepolcro, il suo corpo luminoso e avvolto da un’aura divina. Attorno a lui, guardie e soldati mostrano sorpresa e sgomento. Giotto utilizza una composizione dinamica e colori vibranti per trasmettere un forte senso di movimento e vita. La scena è ricca di emozione e simboleggia la vittoria sulla morte, rendendo visibile l’umanità di Cristo e la speranza della resurrezione per l’umanità intera.

L’orazione nell’orto di Tintoretto – La Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Venezia, (ca. 1500)

E’ un’opera monumentale che rappresenta la scena dell’agonia di Gesù nel Getsemani. La composizione è caratterizzata da forte contrasto di luci e ombre, creando un’atmosfera drammatica e intensa. Gesù, al centro dell’opera, è ritratto in un momento di profonda meditazione e tristezza, mentre gli apostoli sono ritratti in posizioni diverse, alcuni in preghiera, altri addormentati. La dinamicità delle figure e l’uso audace della prospettiva conferiscono movimento e profondità all’intera scena. La tavolozza ricca e i dettagli accurati riflettono la maestria del Tintoretto nel catturare l’emozione e la spiritualità del momento.

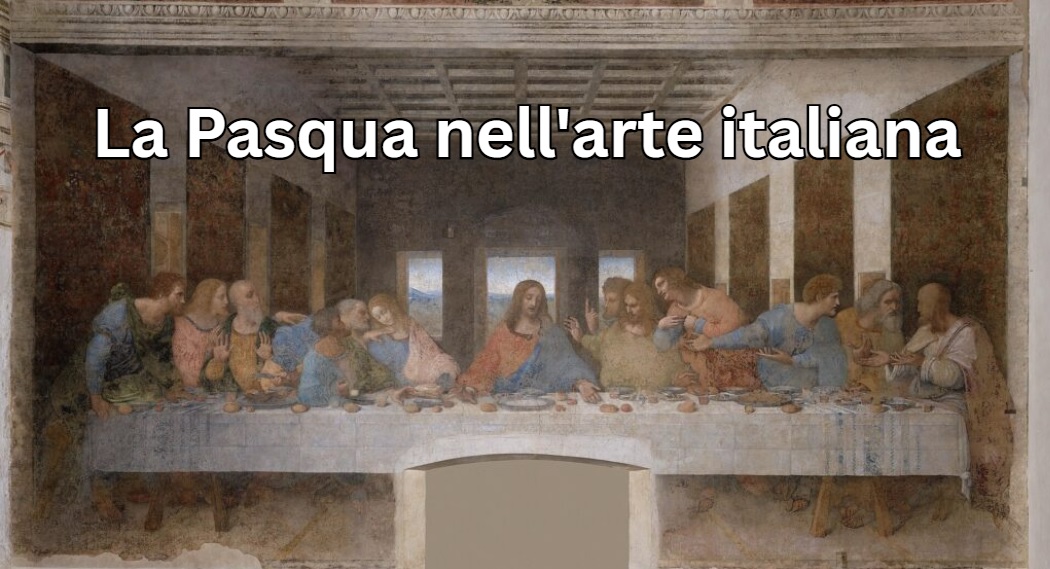

L’Ultima cena di Leonardo da Vinci – Santa Maria delle Grazie, Refettorio, Milano (c. 1495-1498)

Sebbene incentrata principalmente sull’Ultima Cena (l’ultimo pasto di Gesù con i suoi discepoli), quest’opera prepara il terreno per gli eventi del Venerdì Santo e della Pasqua, mostrando l’attesa della crocifissione e della resurrezione.

L’opera rappresenta il momento in cui Gesù annuncia il tradimento di Giuda, catturando le reazioni diverse dei discepoli. L’uso della prospettiva e la composizione dinamica creano profondità e intensità emotiva. I volti esprimono incredulità, rendendo questa scena una delle più celebri e influenti della storia dell’arte.

Cristo (deriso) dopo la cattura di Beato Angelico – Covento di San Marco, Firenze (ca. 1500)

E’ un’opera che cattura l’intensità del momento in cui Gesù viene arrestato. L’immagine dello sputo, simbolo di disprezzo, sottolinea la brutalità della sofferenza che Cristo deve affrontare. La scena mostra Gesù legato e circondato da due figure che esprimono smarrimento e pietà. La delicatezza e la luce della scena, tipiche dello stile di Beato Angelico, offrono un contrasto stridente con il tema della violenza.

Crocefissione di Angelo Italia – La Cappella del Crocefisso, Monreale, (1680)

E’ un’opera d’arte straordinaria che riflette la maestria dell’artista e la spiritualità dell’epoca. La composizione rappresenta il momento culminante della Passione di Cristo, con il protagonista crocifisso tra i ladroni. La scena è ricca di dettagli espressivi, mostrando un forte contrasto tra la sofferenza di Gesù e la drammaticità del contesto. I colori vividi e l’uso sapiente della luce conferiscono profondità all’opera, rendendo palpabile il sentimento di sacrificio. La cappella, con i suoi affreschi e mosaici, rappresenta un importante esempio di arte sacra normanna.

La Crocefissione di Andrea Mantegna – Museo del Louvre, Parigi (c. 1350-1406)

La Crocefissione di Andrea Mantegna è un’opera straordinaria che trasmette un intenso senso di drammaticità e sofferenza attraverso la sua composizione verticale e l’uso audace della prospettiva. Il Cristo crocifisso è al centro, rappresentato con un realismo crudo, mentre la sua figura è accentuata da ombre profonde e colori terrosi. I personaggi ai suoi piedi, tra cui la Vergine Maria e San Giovanni, esprimono angoscia e lutto. Mantegna utilizza dettagli anatomici precisi e una forte definizione spaziale, creando una scena che invita lo spettatore a riflettere sulla sofferenza e sulla redenzione.

Compianto sul Cristo Morto di Niccolò dell’Arca -Chiesa di Santa Maria della Vita, Bologna (ca. 1477, rinascimento)

E’ gruppo scultoreo con sette figure a grandezza naturale in terracotta con tracce di policromia. L’opera rappresenta la drammatica scena della deposizione di Cristo, con una composizione intensa e marcata da emozione. Le figure, altamente espressive, mostrano il dolore e la sofferenza, mentre il corpo di Cristo, con dettagli anatomici raffinati, appare pesante e cadente. Il gruppo scultoreo, con una forte verticalità, crea un contrasto tra il sacro e l’umano, evidenziando la tragedia della morte. L’uso del colore e della luce rende la scena ancora più coinvolgente.

Cristo Morto di Andrea Mantegna – Pinacoteca di Brera, Milano (c. 1480)

E’ un capolavoro dell’arte rinascimentale. Il dipinto ritrae il corpo di Cristo disteso su una lastra di pietra, con un’espressiva resa anatomica e un forte senso del realismo. La composizione, caratterizzata da un’angolazione innovativa, invita lo spettatore a contemplare la vulnerabilità e il sacrificio del Cristo. L’opera è celeberrima per il vertiginoso scorcio prospettico della figura del Cristo disteso, che ha la particolarità di “seguire” lo spettatore che ne fissi i piedi scorrendo davanti al quadro stesso.

Elementi drammatici, come le mani e i piedi forati, accentuano il dolore, mentre il fondo scuro mette in risalto la figura centrale. Mantegna esplora così temi di morte e redenzione.

La Pietà di Michelangelo – Basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano (ca. 1499)

E’ una delle opere più celebri del Rinascimentoun, capolavoro di straordinaria espressione emotiva. La scultura in marmo rappresenta la Vergine Maria che tiene in grembo il corpo di Gesù morto, esprimendo un profondo senso di tristezza e pietà. Michelangelo scolpì la figura con una straordinaria precisione anatomica e un’armonia delle proporzioni, creando un effetto di serenità e bellezza. La drammaticità dell’opera è accentuata dai dettagli delicati e dall’uso della quarzite, che conferisce una morbidezza unica.

Il Cristo Velato di Giuseppe San Martino – Cappella San Severo, Napoli (1752)

Questa straordinaria opera d’arte rappresenta il corpo di Cristo deposto, avvolto in un velo di marmo trasparente, che sembra sorgere alla vita. La maestria tecnica di San Martino si manifesta nella straordinaria resa dei dettagli: il velo appare leggero e traslucido, mentre il corpo di Cristo esprime serenità nella morte. L’opera è un simbolo di pietà e fede, e la sua bellezza e realismo suscitano emozioni profonde in chi la osserva, rendendola un capolavoro del barocco napoletano.

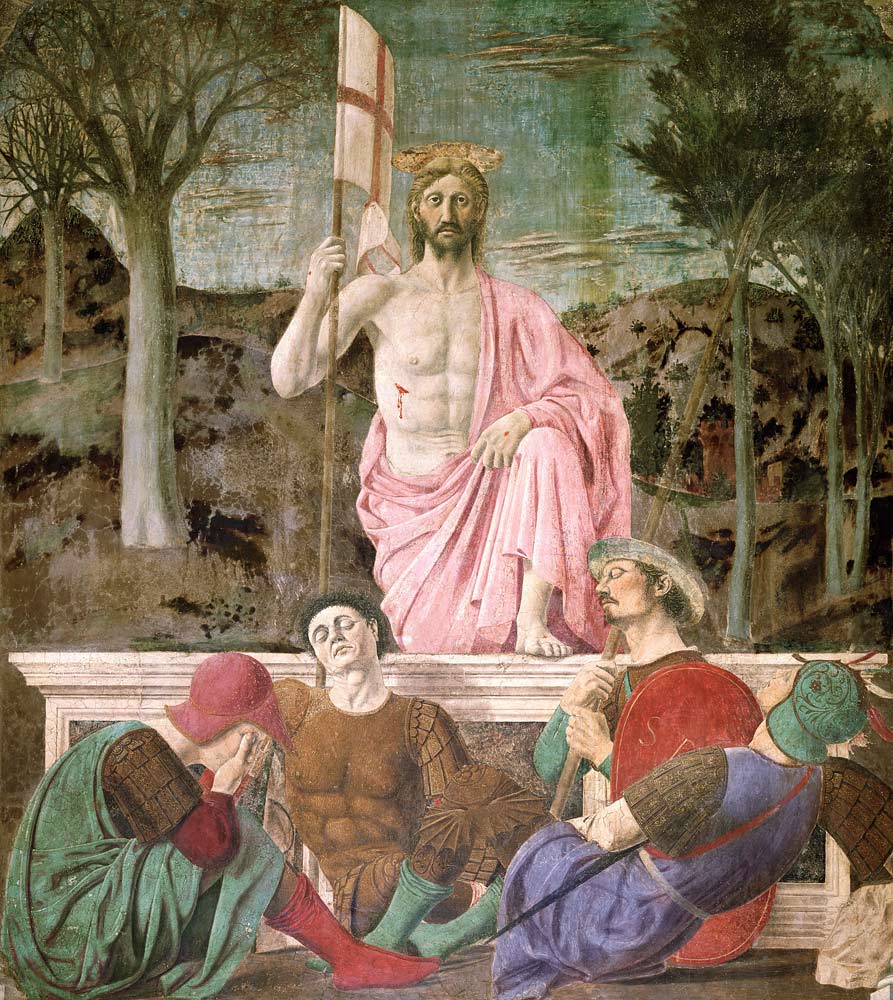

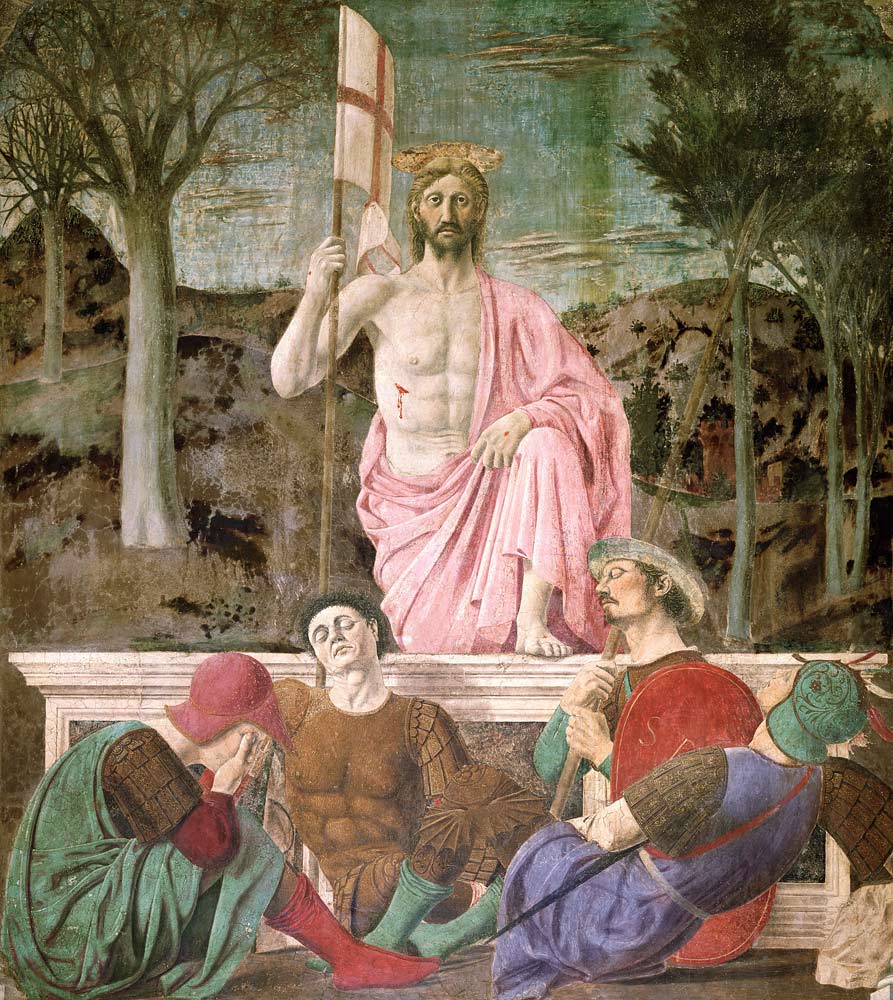

Resurrezione di Piero della Francesca, Borgo San Sepolcro, Arezzo (c. 1465)

L’opera rappresenta Cristo che, risorto dai morti, emerge in un potente gesto di vittoria, circondato da un delicato aura di luce. Il corpo di Cristo è colto in una naturalezza monumentale, con un espressione serena e regale. Sullo sfondo, il paesaggio si estende in un armonioso equilibrio di colori, mentre i soldati addormentati ai suoi piedi simboleggiano l’ignavia umana di fronte al divino. La composizione rigorosa e l’uso innovativo della prospettiva evidenziano la maestria dell’artista, fondendo spiritualità e bellezza.

Il Trionfo del Nome di Gesù di Giovanni Battista Gaulli (Il Baciccio) – Chiesa del Gesù, Roma (c. 1672)

Affresco sul soffitto che si collega alla natura celebrativa della Pasqua con una gloriosa celebrazione della divinità di Gesù, attraerso una composizione dinamica e teatrale. Al centro si staglia il monogramma di Gesù, circondato da angeli, santi e figure celestiali che si librano nell’aria, immersi in una luce divinamente radiosa. I colori vibranti e il senso di movimento esprimono la maestà e la potenza del nome di Gesù, riflettendo il barocco romano e la spiritualità dell’epoca.

Alcune di queste opere d’arte sono spiegate con approfondimenti delle tecniche artistiche nel video seguente: https://youtu.be/8cnr_VEjF84?si=dOz9Xb4ZqYyWPxQD

English version

Religious art in Italian museums represents an invaluable heritage that reflects the country’s profound spirituality and cultural history. Works by masters such as Michelangelo, Caravaggio and Giotto adorn the galleries, testifying to centuries of devotion and artistic innovation. Sculptures, paintings and frescoes tell biblical stories, saints and local traditions, immersed in a context of beauty and contemplation. Museums, such as the Uffizi in Florence or the Vatican Museums in Rome, preserve these works with care, allowing visitors to explore the connection between art and faith, uniting the sacred with aesthetic contemplation.

Italian art is rich in works related to the themes of Easter, which reflect the crucial moments of the Christian narrative. These twelve famous Italian works of art related to Easter highlight the theological and artistic meaning of Easter in the context of the Italian Renaissance and Baroque, offering a profound reflection on the themes of resurrection, salvation and hope.

Resurrection, Giotto – Scrovegni Chapel, Padua (ca. 1303)

depicting the resurrected Christ, is an integral part of the Easter story.

Giotto’s Resurrection, frescoed in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, is an extraordinary work that testifies to the artist’s mastery. Located in the upper part of the apse, it depicts Christ emerging triumphant from the tomb, his body luminous and enveloped in a divine aura. Around him, guards and soldiers show surprise and dismay. Giotto uses a dynamic composition and vibrant colors to convey a strong sense of movement and life. The scene is full of emotion and symbolizes the victory over death, making visible the humanity of Christ and the hope of resurrection for all humanity.

The Agony in the Garden, Tintoretto – Scuola Grande di San Rocco, Venice, (ca. 1500)

It is a monumental work that represents the scene of Jesus’ agony in Gethsemane. The composition is characterized by strong contrasts of light and shadow, creating a dramatic and intense atmosphere. Jesus, at the center of the work, is portrayed in a moment of deep meditation and sadness, while the apostles are portrayed in different positions, some in prayer, others asleep. The dynamism of the figures and the bold use of perspective give movement and depth to the entire scene. The rich palette and accurate details reflect Tintoretto’s mastery in capturing the emotion and spirituality of the moment.

The Last Supper, Leonardo da Vinci – Santa Maria delle Grazie, Refectory, Milan (c. 1495-1498)

Although primarily focused on the Last Supper (Jesus’ final meal with his disciples), this work sets the stage for the events of Good Friday and Easter, showing the anticipation of the crucifixion and resurrection.

The work depicts the moment when Jesus announces Judas’ betrayal, capturing the disciples’ varying reactions. The use of perspective and dynamic composition create depth and emotional intensity. The faces express disbelief, making this scene one of the most famous and influential in the history of art.

Christ (Mocked) After the Capture, Beato Angelico – Convent of San Marco, Florence (ca. 1500)

This work captures the intensity of the moment when Jesus is arrested. The image of spitting, a symbol of contempt, underlines the brutality of the suffering that Christ must face. The scene shows Jesus tied up and surrounded by two figures expressing bewilderment and pity. The delicacy and light of the scene, typical of Beato Angelico’s style, offer a stark contrast to the theme of violence.

Crucifixion, Angelo Italia – The Chapel of the Crucifix, Monreale, (1680)

It is an extraordinary work of art that reflects the artist’s mastery and the spirituality of the time. The composition represents the culminating moment of the Passion of Christ, with the protagonist crucified among the thieves. The scene is rich in expressive details, showing a strong contrast between the suffering of Jesus and the drama of the context. The vivid colors and the skillful use of light give depth to the work, making the feeling of sacrifice palpable. The chapel, with its frescoes and mosaics, represents an important example of Norman sacred art.

The Crucifixion, Andrea Mantegna – Louvre Museum, Paris (c. 1350-1406)

The Crucifixion by Andrea Mantegna is a stunning work that conveys an intense sense of drama and suffering through its vertical composition and bold use of perspective. The crucified Christ is at the center, depicted with stark realism, his figure accentuated by deep shadows and earthy colors. The figures at his feet, including the Virgin Mary and Saint John, express anguish and mourning. Mantegna uses precise anatomical details and strong spatial definition, creating a scene that invites the viewer to reflect on suffering and redemption.

Lamentation over the Dead Christ, Niccolò dell’Arca – Church of Santa Maria della Vita, Bologna (ca. 1477, Renaissance)

It is a sculptural group with seven life-size figures in terracotta with traces of polychromy. The work represents the dramatic scene of the deposition of Christ, with an intense and emotional composition. The highly expressive figures show pain and suffering, while the body of Christ, with refined anatomical details, appears heavy and drooping. The sculptural group, with a strong verticality, creates a contrast between the sacred and the human, highlighting the tragedy of death. The use of color and light makes the scene even more engaging.

Dead Christ, Andrea Mantegna – Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan (c. 1480)

It is a masterpiece of Renaissance art. The painting depicts the body of Christ lying on a stone slab, with an expressive anatomical rendering and a strong sense of realism. The composition, characterized by an innovative angle, invites the viewer to contemplate the vulnerability and sacrifice of Christ. The work is very famous for the dizzying perspective view of the figure of the reclining Christ, which has the peculiarity of “following” the viewer who stares at his feet, flowing in front of the painting itself.

Dramatic elements, such as the pierced hands and feet, accentuate the pain, while the dark background highlights the central figure. Mantegna thus explores themes of death and redemption.

Pietà, Michelangelo – St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican (ca. 1499)

It is one of the most famous works of the Renaissance, a masterpiece of extraordinary emotional expression. The marble sculpture represents the Virgin Mary holding the body of the dead Jesus in her lap, expressing a deep sense of sadness and pity. Michelangelo sculpted the figure with extraordinary anatomical precision and harmony of proportions, creating an effect of serenity and beauty. The drama of the work is accentuated by the delicate details and the use of quartzite, which gives it a unique softness.

The Veiled Christ, Giuseppe San Martino – San Severo Chapel, Naples (1752)

This extraordinary work of art represents the body of Christ laid down, wrapped in a transparent marble veil, which seems to come to life. San Martino’s technical mastery is evident in the extraordinary rendering of details: the veil appears light and translucent, while the body of Christ expresses serenity in death. The work is a symbol of piety and faith, and its beauty and realism arouse deep emotions in those who observe it, making it a masterpiece of Neapolitan Baroque.

Resurrection, Piero della Francesca, Borgo San Sepolcro, Arezzo (c. 1465)

The work represents Christ who, risen from the dead, emerges in a powerful gesture of victory, surrounded by a delicate aura of light. The body of Christ is captured in a monumental naturalness, with a serene and regal expression. In the background, the landscape extends in a harmonious balance of colors, while the sleeping soldiers at his feet symbolize human indolence in the face of the divine. The rigorous composition and the innovative use of perspective highlight the artist’s mastery, merging spirituality and beauty.

The Triumph of the Name of Jesus, Giovanni Battista Gaulli (Il Baciccio) – Church of the Gesù, Rome (c. 1672)

A ceiling fresco that connects to the celebratory nature of Easter with a glorious celebration of the divinity of Jesus, through a dynamic and theatrical composition. The monogram of Jesus stands out in the center, surrounded by angels, saints and celestial figures hovering in the air, bathed in a divinely radiant light. The vibrant colors and sense of movement express the majesty and power of the name of Jesus, reflecting the Roman Baroque and spirituality of the era.

Some of these works of art are explained with insights into the artistic techniques in the following video: https://youtu.be/8cnr_VEjF84?si=dOz9Xb4ZqYyWPxQD

- Racconto italiano: Gatti e cani comandano il mondo?/A2-B1

- Come studiare l’italiano in estate o in vacanza?

- Racconto italiano: La magia dell’arte/A2-B1

- Racconto italiano: La torre dell’orologio/A2-B1

- Racconto italiano: Il labirinto di Lucca/B1

- Racconto italiano: Il segreto per imparare l’italiano/B1

- La Pasqua nell’arte italiana

- Racconto italiano: La disdetta del frullato al cacao A2/B1

- Come si usa il gerundio