(English follows)

Ascolta l’articolo (versione avanzata C1):

Ascolta la versione B1:

“Nella vita non bisogna mai rassegnarsi, arrendersi alla mediocrità, bensì uscire da quella zona grigia in cui tutto è abitudine e rassegnazione passiva, bisogna coltivare il coraggio di ribellarsi.” – Rita Levi-Montalcini

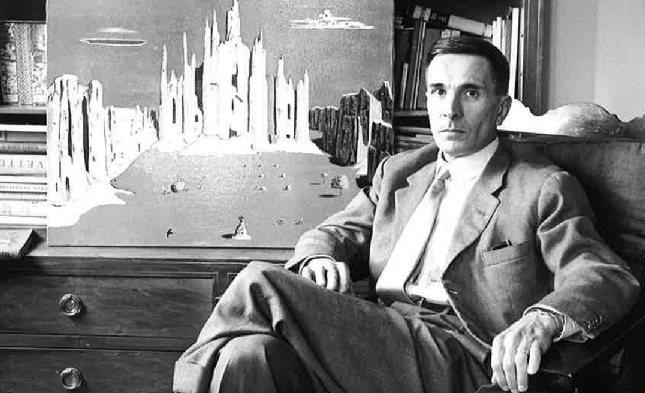

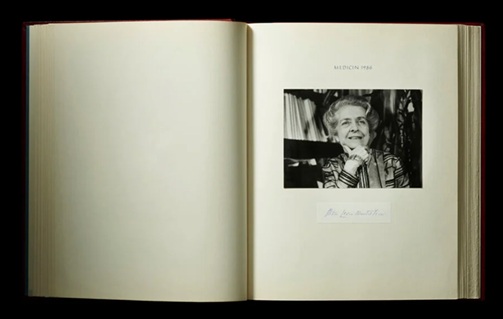

Rita Levi-Montalcini è stata una delle neuroscienziate più importanti del XX secolo, nota per le sue scoperte fondamentali nel campo della biologia e del sistema nervoso. Nata il 22 aprile 1909 a Torino, Rita ha affrontato molte sfide nel corso della sua vita, tra cui le discriminazioni di genere e l’antisemetismo, ma grazie alla sua determinazione è diventata una figura di rilievo nel campo scientifico a livello internazionale.

Foto: Copyright sconosciuto

Figlia di una colta famiglia ebrea, Rita ha mostrato sin dalla giovane età un grande interesse per la scienza e la natura. A 20 anni si rese conto che non poteva adattarsi al ruolo femminile concepito da suo padre e gli chiesi il permesso di intraprendere una carriera professionale.

Lo convinse a lasciarla studiare medicina e imparò greco, latino e matematica in soli otto mesi, per poi iscriversi alla facoltà di medicina all’Università di Torino. Dopo la laurea in medicina e chirurgia nel 1936 con il massimo dei voti, non era più certa di voler diventare medico, ispirata dal professore, istologo e ricercatore Giuseppe Levi.

Iniziò cosi studi avanzati in neurologia e psicologia, ma fu presto espulsa quando le leggi razziali di Mussolini del 1938 proibirono a chiunque non fosse ariano di intraprendere una carriera professionale o accademica. Si recò a Bruxelles per un breve periodo per studiare presso un istituto neurologico, ma dovette fuggire prima dell’invasione del Belgio da parte della Germania.

“Rifiutate di accedere a una carriera solo perché vi assicura una pensione. La migliore pensione è il possesso di un cervello in piena attività che vi permetta di continuare a pensare ‘usque ad finem’, ‘fino alla fine’.” – Rita Levi-Montalcini

Tornò a Torino dove si dedicò intensamente alla ricerca scientifica, nonostante il divieto di mettere piede all’università. Costruì un laboratorio nella sua camera da letto, realizzando bisturi con aghi da cucito, usando minuscole forbici da oculista e pinze da orologiaio. Dopo aver letto un articolo dell’embriologo Viktor Hamburger, dissezionò embrioni di pollo e ne studiò al microscopio i motoneuroni, cellule nervose responsabili del controllo del movimento.

Assunse persino un assistente, Giuseppe Levi, il suo mentore alla facoltà di medicina, anch’egli espulso dall’accademia per motivi religiosi. Insieme a Giuseppe Levi, elaborò una teoria sulle cellule nervose embrionali, secondo cui proliferano, iniziano a crescere e poi muoiono, il che contrastava con il modello descritto nell’articolo di Viktor Hamburger. Quella teoria pose le basi per il concetto moderno di morte delle cellule nervose come parte del loro normale sviluppo. Essendo ebrei, non potevano pubblicare su riviste italiane, tuttavia i loro risultati furono pubblicati su riviste straniere all’inizio degli anni ’40.

Quando gli Alleati bombardarono Torino, Rita trasferì il suo laboratorio improvvisato in campagna. Allorché i tedeschi invasero e iniziarono a rastrellare gli ebrei, lei e la sua famiglia si trasferirono a sud dove sopravvissero sotto falsi nomi. Alla fine della guerra curò per breve tempo i pazienti in un campo profughi. La Levi-Montalcini sapeva che la ricerca in neuroembriologia sarebbe stata la sua strada, la quale le fu assicurata nel 1946, quando Viktor Hamburger, incuriosito dai suoi risultati contrastanti, la invitò alla Washington University di St. Louis, nel Missouri. “Mi sentii a casa il giorno in cui atterrai”, scrisse in seguito. Ci sarebbe rimasta per 30 anni.

Nel 1948, la Levi-Montalcini scoprì che un tipo di tumore murino stimolava la crescita dei nervi negli embrioni di pollo. Insieme ad Hamburger, capirono che la causa era una sostanza nel tumore, chiamata fattore di crescita nervoso (NGF), una proteina fondamentale per la crescita e la differenziazione delle cellule nervose. Il tumore provocava la crescita di cellule nervose anche in laboratorio. In seguito il biochimico Stanley Cohen, suo collega, riuscì a isolare l’NGF. Rita Levi-Montalcini vinse il Premio Nobel per la Medicina nel 1986, condiviso con Stanley Cohen, per la scoperta del fattore di crescita nervoso (NGF). Studiando l’NGF gli scienziati hanno meglio capito la crescita neurale e come potenzialmente combattere malattie neurodegenerative, e trattare malattie come lAlzheimer, demenza, cancro, sclerosi multipla, schizofrenia e autismo.

Oltre alla sua attività scientifica, Rita Levi-Montalcini si impegnò anche nel promuovere i diritti delle donne e dedicò in particolar modo l’ultima parte della sua carriera a garantire che altri scienziati avessero accesso a fondi, attrezzature e supporto. Ad esempio, ha fondato e diretto l’Istituto di Biologia Cellulare di Roma. Ha fondato l’Istituto Europeo di Ricerca sul Cervello nel 2002. Ha inoltre istituito la Fondazione Rita Levi-Montalcini, per fornire alle donne africane “gli strumenti per un pieno sviluppo delle loro capacità”.

“Le donne hanno sempre dovuto lottare doppiamente. Hanno sempre dovuto portare due pesi, quello privato e quello sociale. Le donne sono la colonna vertebrale delle società.”

Nel 2001 ricevette una delle più alte onorificenze italiane, diventando senatrice a vita, un ruolo che non prese alla leggera. Nel 2006, all’età di 97 anni, fu lei a detenere il voto decisivo in Parlamento in una controversia sul bilancio. Minacciò di ritirare il suo sostegno al governo se non avesse revocato la decisione di tagliare i fondi per la scienza. Nonostante i tentativi dell’opposizione di metterla a tacere prendendola in giro per la sua età, i fondi furono reintegrati e il bilancio fu approvato. Per la Levi-Montalcini, le sfide erano una motivazione.

Rita Levi-Montalcini si spense all’età di 103 anni il 30 dicembre 2012 a Roma, lasciando un’eredità duratura nel campo della scienza e dell’umanità.

“Ho perso un po’ la vista, molto l’udito. Alle conferenze non vedo le proiezioni e non sento bene. Ma penso più adesso di quando avevo vent’anni. Il corpo faccia quello che vuole. Io non sono il corpo: io sono la mente.”

English version:

“In life, you must never resign yourself or surrender to mediocrity. Instead, you must escape that gray area where everything is habit and passive resignation. You must cultivate the courage to rebel.”

Rita Levi-Montalcini was one of the most important neuroscientists of the 20th century, known for her fundamental discoveries in biology and the nervous system. Born on April 22, 1909, in Turin, Rita faced many challenges throughout her life, including gender discrimination and anti-Semitism, but thanks to her determination, she became an internationally prominent figure in science.

The daughter of a cultured Jewish family, Rita showed a keen interest in science and nature from a young age. At 20, she realized she could not fit into the feminine role her father had conceived and asked him for permission to pursue a professional career.

She convinced him to let her study medicine, and she learned Greek, Latin, and mathematics in just eight months, before enrolling in medical school at the University of Turin. After graduating in medicine and surgery in 1936 with honors, she was no longer sure she wanted to become a doctor, inspired by professor, histologist, and researcher Giuseppe Levi.

She began advanced studies in neurology and psychology, but was soon expelled when Mussolini’s racial laws of 1938 prohibited anyone who was not Aryan from pursuing a professional or academic career. She went to Brussels for a short time to study at a neurological institute, but had to flee before the German invasion of Belgium.

“Refuse to enter a career just because it guarantees you a pension. The best pension is the possession of a fully functioning brain that allows you to continue thinking ‘usque ad finem,’ ‘until the end.'”

She returned to Turin, where she devoted herself intensely to scientific research, despite being forbidden to set foot in the university. He built a laboratory in his bedroom, making scalpels out of sewing needles, using tiny ophthalmologist scissors and watchmaker’s pliers. After reading an article by embryologist Viktor Hamburger, he dissected chicken embryos and studied their motor neurons, the nerve cells responsible for controlling movement, under a microscope.

He even hired an assistant, Giuseppe Levi, his mentor at medical school, who had also been expelled from the academy for religious reasons. Together with Giuseppe Levi, he developed a theory of embryonic nerve cells, according to which they proliferate, begin to grow, and then die, which conflicted with the model described in Viktor Hamburger’s article. This theory laid the foundation for the modern concept of nerve cell death as part of their normal development. Because they were Jewish, they could not publish in Italian journals, yet their results were published in foreign journals in the early 1940s.

When the Allies bombed Turin, Rita moved her makeshift laboratory to the countryside. When the Germans invaded and began rounding up Jews, she and her family moved south, where they survived under assumed names. At the end of the war, she briefly treated patients in a refugee camp. Levi-Montalcini knew that research in neuroembryology would be her path, which was assured in 1946 when Viktor Hamburger, intrigued by her conflicting results, invited her to Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. “I felt at home the day I landed,” she later wrote. She would remain there for 30 years.

In 1948, Levi-Montalcini discovered that a type of mouse tumor stimulated nerve growth in chick embryos. Together with Hamburger, they identified the cause as a substance in the tumor called nerve growth factor (NGF), a protein essential for the growth and differentiation of nerve cells. The tumor also caused nerve cells to grow in the laboratory. Later, her colleague, biochemist Stanley Cohen, succeeded in isolating NGF. Rita Levi-Montalcini won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1986, shared with Cohen, for the discovery of nerve growth factor (NGF). By studying NGF, scientists better understood neural growth and how it could potentially combat neurodegenerative diseases and treat conditions such as Alzheimer’s, dementia, cancer, multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia, and autism.

In addition to her scientific work, Rita Levi-Montalcini was also committed to promoting women’s rights and dedicated the latter part of her career to ensuring that other scientists had access to funding, equipment, and support. For example, she founded and directed the Institute of Cell Biology in Rome. She founded the European Brain Research Institute in 2002. She also established the Rita Levi-Montalcini Foundation to provide African women “with the tools to fully develop their capabilities.”

“Women have always had to struggle twice. They have always had to bear two burdens: the private and the social. Women are the backbone of societies.”

In 2001, she received one of Italy’s highest honors, becoming a senator for life, a role she did not take lightly. In 2006, at the age of 97, she held the deciding vote in Parliament in a budget dispute. She threatened to withdraw her support for the government unless it reversed its decision to cut science funding. Despite the opposition’s attempts to silence her by mocking her age, the funding was reinstated and the budget was approved. For Levi-Montalcini, challenges were a motivation.

Rita Levi-Montalcini died at the age of 103 on December 30, 2012, in Rome, leaving a lasting legacy in science and humanity.

“I’ve lost a little of my sight, a lot of my hearing. At conferences, I can’t see the projections, and I can’t hear well. But I think more now than I did when I was twenty. The body can do what it wants. I am not the body: I am the mind.”

- Rita Levi Montalcini, Premio Nobel per la Fisiologia o la Medicina 1986

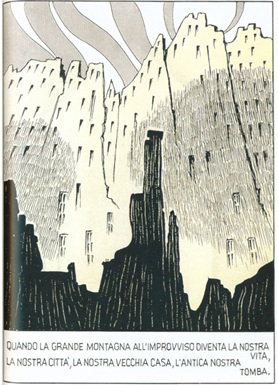

- Dino Buzzati, il pittore scrittore italiano del XX secolo

- Sciare a Cortina d’Ampezzo e non solo

- Racconto italiano: Giano, il dio dei passaggi A2/B1

- Racconto italiano: Il pupazzo di neve A1/A2

- Racconto italiano: Un paesino disabitato / A2-B1

- L’autunno nella lingua italiana: espressioni popolari

- Racconto italiano: Un sabato indaffarato / A2

- Racconto italiano: Dove sono le mie forbici? / B1