La letteratura era una delle mie materie preferite a scuola. Tuttavia, quando ero più giovane non ero consapovole del fatto che i nostri libri di scuola trascurassero le scrittrici italiane. Leggevamo Machiavelli, Dante, Calvino, ma nei nostri pesanti volumi non c’era menzione di Alda Merini, Natalia Ginzburg, Elsa Morante, Anna Maria Ortese, Matilde Serao, Maria Messina,….

Pensavo che non esistessero scrittrici italiane ed è un peccato che le giovani ragazze italiane in particolare non siano a conoscenza delle menti creative femminili del nostro passato. Ho scoperto Maria Messina solo di recente, e mi chiedo quanto avesse potuto essere influente il suo lavoro durante i miei anni formativi.

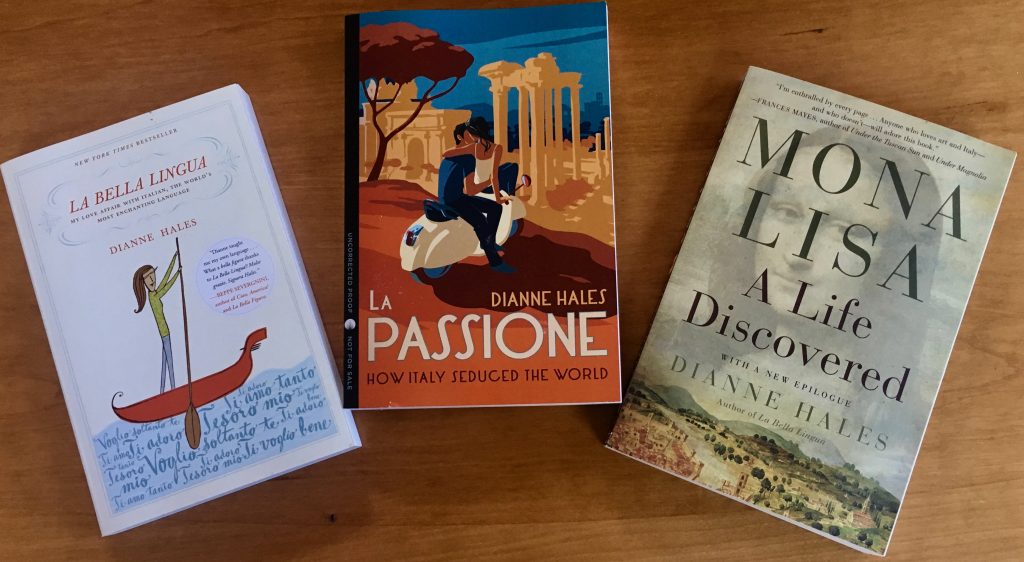

Literature was one of my favorite subjects in school. However, little did I know when I was younger that our school books neglected to include Italian female writers. We read Machiavelli, Dante, Calvino, but there was no mention in our thick tomes of Alda Merini, Natalia Ginzburg, Elsa Morante, Matilde Serao, Maria Messina,….

I used to think that there weren’t any female Italian writers and it is a shame that young Italian girls in particular are not aware of the female creative minds of our past. I only discovered Maria Messina recently, and it makes me wonder how influential her work could have been during my formative year.

Maria Messina nacque in provincia di Palermo nel 1887 e fu autodidatta. Il fratello maggiore la incoraggiò ad intraprendere la carriera di scrittrice e all’età di ventidue anni iniziò un’intensa corrispondenza con Giovanni Verga. Pubblicò poi una serie di racconti tra il 1909 e il 1921, tra cui una novella, Luciuzza, pubblicata nel 1914 su una rivista letteraria chiamata Nuova Antologia, grazie al sostegno di Verga. Per molti anni visse a Mistretta, un piccolo paese adagiato sui Monti Nebrodi, dove sono ambientate molte delle sue storie.

Sembra che il suo nome abbia iniziato a svanire lentamente e gradualmente dopo la sua morte prematura, e di conseguenza i suoi libri sono andati fuori stampa, dimenticati dalla storia letteraria del Novecento.

Per fortuna nel 1980 fu riscattata dall’oblio e riscoperta da Leonardo Sciascia, tanto che molte sue opere sono state ripubblicate. Ora è tra le scrittrici più celebri del primo Novecento, ed è inclusa nel progetto Le Autrici della Letteratura Italiana. Dal 1986 i suoi libri sono stati tradotti in francese, tedesco, inglese e spagnolo.

Maria Messina was born in the province of Palermo in 1887 and was self-educated. Her older brother encouraged her to begin a writing career and at the age of twenty-two she began an intense correspondence with Giovanni Verga. She then published a series of short stories between 1909 and 1921, among which a novella, Luciuzza, published in 1914 in a literary magazine called Nuova Antologia, thanks to Verga’s support. For many years, she lived in Mistretta, a small town nestled in the Nebrodi Mountains, where many of her stories are set.

It seems that her name started to fade slowly and gradually after her premature death, so her books went out of print. Forgotten by the literary history of the twentieth century. Luckily in 1980 she was redeemed from oblivion and rediscovered by Leonardo Sciascia so that many of her works were republished. She is now among the most celebrated woman writers of the early 20th century, and is included in The Women Authors of Italian Literature project. Since 1986 her books have been translated into French, German, English, and Spanish.

Tra i temi principali di Messina vi sono l’isolamento e l’oppressione delle giovani donne in Sicilia e nella cultura siciliana. Inoltre, i suoi scritti si concentrano sul dominio maschile e sulla sottomissione femminile che sono inerenti alle relazioni affettive. Il romanzo “La casa nel vicolo” segnò una svolta importante nella scrittura messinese, poiché si avvaleva di condizioni psicologiche. Alcuni credono che Messina non fosse una femminista poiché presentava l’oppressione delle donne come inevitabile e ciclica. Anche se fosse, le sue donne rappresentano potenti dichiarazioni di sfida.

Di recente ho letto “Ragazze siciliane”, pubblicato originariamente nel 1921 dall’editore Le Monnier di Firenze, che comprende 8 racconti i cui temi riguardano, come commenta la stessa autrice in una nota dell’autunno 1920, “figlie di poveri dipendenti e piccoli proprietari […] che abitano in paesini piccoli, chiusi e remoti, dove l’abitudine scandisce un ritmo uguale, dove le notizie e i rumori arrivano tardi, come voci attutite dalla lontananza”. Eppure, anche loro, «pur continuando a camminare nei sentieri tracciati dall’esperienza degli anziani, sognando bambini da cullare, una casa da gestire… parlano del desiderio di libertà».

Among Messina’s main themes are the isolation and oppression of young women in Sicily and in Sicilian culture. Additionally, her writing focuses on male dominance and female submission that are inherent to emotional relationships. The novel “La casa nel vicolo” marked an important turning point in Messina’s writing, as it made use of psychological conditions. Some believe Messina was not a feminist since she presented the oppression of women as inevitable and cyclical. Even so, her women represent powerful statements of challenge.

I’ve recently been reading “Sicilian girls”, originally published in 1921 by the publisher Le Monnier of Florence, which includes 8 short stories whose themes concern, as the author herself commented in a note dated autumn 1920, “daughters of poor employees and small owners […] who live in small, closed and remote villages, where habit marks an equal rhythm, where news and noise arrive late, like voices muffled by distance “. Yet, even they, “while continuing to walk in the paths traced by the experience of the elderly, dreaming of babies to be cradled, a house to be managed … they speak of the desire for freedom.”

Maria Messina apre le porte di un mondo mediocre, chiuso nel proprio egoismo e resistente a ogni cambiamento, un mondo piccolo borghese la cui unica preoccupazione è salvare la faccia di fronte alla comunità di cui fa parte. Non è facile evadere da questo universo ristretto e spesso meschino, soprattutto per chi, come le donne che descrive, non è in grado di esercitare la propria libertà interiore. Le “prigioni” che descrive, che racchiudono sia le vittime che i persecutori, sono i circoli chiusi all’interno dei quali i protagonisti si vedono vivere. Nella rinuncia, nella resa, nell’accettazione di ciò che è considerato ineluttabile, non c’è debolezza o accidia, ma il segno di una realtà da scontare.

Dopo aver letto in “Ragazze siciliane” il racconto straziante di una bambina di nome Luciuzza, abbandonata nelle mani dei parenti dopo la prematura scomparsa della madre, mi chiedo quanto di quel mediocre mondo dipinto da Maria Messina appartenga al passato e quanto sia in realtà abilmente nascosto ai nostri giorni.

Maria Messina opens the doors of a mediocre world, closed in its own selfishness and resistant to any change, a world of petty bourgeois whose only concern is to save face in the face of the community to which it belongs. It is not easy to escape from this restricted and often petty universe, especially for those who, like the women she describes, are unable to exercise their inner freedom. The “prisons” she describes, which enclose both the victims and the persecutors, are the closed circles within which the protagonists see themselves living. In the renunciation, in the surrender, in the acceptance of what is considered ineluctable, there is no weakness or sloth, but the sign of a reality to be discounted.

After reading in “Sicilian girls” the wrenching short story of a little girl named Luciuzza, abandoned to her relatives after the premature death of her mother, I wondered how much of that mediocre world depicted by Maria Messina belongs to the past and how much is actually shrewdly concealed in our modern day.

- Il Discorso diretto e discorso indiretto in italiano

- I massacri delle foibe – Il Giorno del Ricordo

- Un racconto di Natale: Il Tesoro dei Poveri di Gabriele D’Annunzio

- Estate di San Martino- leggenda e tradizioni

- I verbi fraseologici: venire/andare a prendere

- Michela Murgia: tenace scrittrice e attivista italiana