by Dianne Hales on August 25, 2014

In this guest post Dianne Hales, author of “La Bella Lingua”, tells us how her new book about La Bella Mona Lisa came to life. At the end of the post you can challenge your knowledge of Mona Lisa with a little quiz that Dianne and I have created for you.

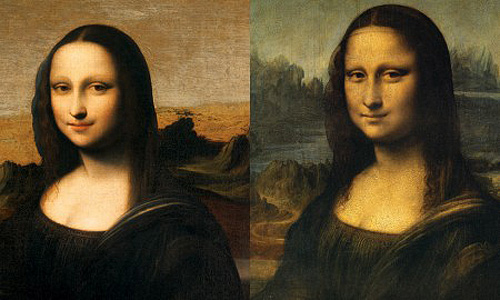

“Earlier Version” and the Louvre Mona Lisa – courtesy of the Mona Lisa Foundation

Her name seduced me. The first time that I heard “Mona (Madame) Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo”— many years after I first beheld Leonardo’s portrait in the Louvre — I repeated the syllables out loud to listen to their Italian sounds. Immediately I felt a surge of curiosity about the woman everyone recognizes but hardly anyone knows.

After falling—happily, gladly, giddily—in love with Italian many years ago, I became just as enamored with the life and times of a true Fiorentina, a daughter of the Renaissance, a merchant’s wife, a loving mother, an artist’s muse and, in her husband’s words, “a noble spirit.” Somehow it seemed only natural to go from a passion for la bella lingua to a quest for una bella donna.

On the trail of Lisa’s story, I followed facts wherever I could find them. I sought the help of authoritative experts in an array of fields, from art to history to sociology to women’s studies. I delved into archives and read through a veritable library of scholarly articles and texts. And I relied on a reporter’s most timeless and trustworthy tool: shoe leather. In the course of extended visits over several years, I walked the streets and neighborhoods of Mona Lisa’s Florence, explored its museums and monuments and came to know—and love—its skies and seasons.

Mona Lisa, I discovered, was a quintessential woman of her times, caught in a whirl of political upheavals, family dramas, and public scandals. Descended from ancient nobles, she was born and baptized in Florence in 1479. Wed to a truculent businessman twice her age, she gave birth to six children and died at age sixty-three in 1542.

Mona Lisa’s life spanned the most tumultuous chapters in the history of Florence, decades of war, rebellion, invasion, siege — and of the greatest artistic outpouring the world has ever seen. Her story creates an extraordinary tapestry of daily life in a vibrant city bursting into fullest bloom.

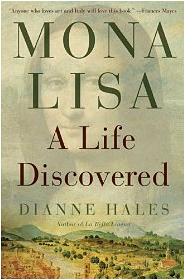

Five centuries after Mona Lisa Gherardini’s death, the world remains eager to learn more about her. Amazon.com chose my book, Mona Lisa: A Life Discovered, published by Simon & Schuster, as one of the “best books of the month” for history and for biography and memoirs. BBC read episodes on the radio for its “Book of the Week” program. CNN and USA Today selected it as one of their “hottest reads” of the summer. Reviewers have praised it as “entertaining,” “enthralling,” “vivid and accessible” and “lyrical.” BRIDES magazine included it on its list of “10 most-read books for your honeymoon.” “Anyone who loves Italy and art—and who doesn’t?—will adore this book,” predicts Frances Mayes, author of Under the Tuscan Sun.

I hope that all of you who love Italian will enjoy this new journey of discovery!

Dianne Hales

Dianne Hales is a prize-winning, widely published journalist and the author of MONA LISA: A Life Discovered. In recognition of her previous book, La Bella Lingua: My Love Affair with Italian, the World’s Most Enchanting Language, as “an invaluable tool for promoting the Italian language,” the President of Italy conferred on Dianne the highest honor its government can bestow on a foreigner, the title of Cavaliere dell’ Ordine della Stella della Solidarietà Italiana (Knight of the Order of the Star of Italian Solidarity.)

Dianne Hales is a prize-winning, widely published journalist and the author of MONA LISA: A Life Discovered. In recognition of her previous book, La Bella Lingua: My Love Affair with Italian, the World’s Most Enchanting Language, as “an invaluable tool for promoting the Italian language,” the President of Italy conferred on Dianne the highest honor its government can bestow on a foreigner, the title of Cavaliere dell’ Ordine della Stella della Solidarietà Italiana (Knight of the Order of the Star of Italian Solidarity.)

You can follow her prize-winning blog on Italy’s language and culture at www.becomingitalianwordbyword.typepad.com and new blog on discovering Mona Lisa at www.monalisabook.com

QUIZ:

0 of 10 questions completed Questions:

Pronti? Via!

You have already completed the quiz before. Hence you can not start it again.

Quiz is loading...

You must sign in or sign up to start the quiz.

You have to finish following quiz, to start this quiz:

0 of 10 questions answered correctly

Your time:

Time has elapsed

You have reached 0 of 0 points, (0) Congratulazioni! La misteriosa Mona Lisa is less mysterious now! If you liked the quiz, share it with your friends. And for more quizzes click here! What does “Mona” mean? “Mona”—spelled “monna” in modern Italian—means “Madame,” a respectful title for married ladies. “Mona”—spelled “monna” in modern Italian—means “Madame,” a respectful title for married ladies. Where was the Mona Lisa first hung? The Mona Lisa was first hung in a French king’s bathing salon. King Francis I, Leonardo’s last patron, bought the portrait for the equivalent of $10 million and hung it in the royal bathing suite at the Palace of Fontainbleau, where the high humidity damaged and dulled its colors. The Mona Lisa was first hung in a French king’s bathing salon. King Francis I, Leonardo’s last patron, bought the portrait for the equivalent of $10 million and hung it in the royal bathing suite at the Palace of Fontainbleau, where the high humidity damaged and dulled its colors. How old was Mona Lisa when she was wed? Mona Lisa was a teenage bride who was wed at age 15 in an arranged marriage to Francesco del Giocondo, a prosperous merchant almost twice her age. Mona Lisa was a teenage bride who was wed at age 15 in an arranged marriage to Francesco del Giocondo, a prosperous merchant almost twice her age. What was Mona Lisa’s last name? Her last name was Lisa Gherardini. She was a real women who descended from a proud, ancient clan who once were rich and powerful Tuscan knights and barons. Her last name was Lisa Gherardini. She was a real women who descended from a proud, ancient clan who once were rich and powerful Tuscan knights and barons. Leonardo Art historians believe that he kept refining and embellishing the painting long after he began the work in 1503. Leonardo kept Lisa’s portrait with him until his death in 1519. Art historians believe that he kept refining and embellishing the painting long after he began the work in 1503. Leonardo kept Lisa’s portrait with him until his death in 1519. What does “Gioconda” mean? Gioconda” means the happy one—a nickname given to the great grandfather of Lisa’s husband, a barrelmaker so merry that all his descendants inherited his nickname. Italians call the Mona Lisa “La Gioconda” as a play on her husband ‘s name and the descriptive for a smiling or jovial woman. Gioconda” means the happy one—a nickname given to the great grandfather of Lisa’s husband, a barrelmaker so merry that all his descendants inherited his nickname. Italians call the Mona Lisa “La Gioconda” as a play on her husband ‘s name and the descriptive for a smiling or jovial woman. How many daughters did Mona Lisa have? She had three daughters—one died at age two and two entered nunneries. She had three daughters—one died at age two and two entered nunneries. Which art historian wrote a biography of Leonardo and his Mona Lisa? Giorgio Vasari’s account of the Mona Lisa comes from his biography of Leonardo published in 1550, 31 years after the artist’s death, and which has long been the best known source of information on the provenance of the work and identity of Leonardo. Giorgio Vasari’s account of the Mona Lisa comes from his biography of Leonardo published in 1550, 31 years after the artist’s death, and which has long been the best known source of information on the provenance of the work and identity of Leonardo. Who commissioned the painting of The Mona Lisa? Leonardo undertook to paint, for Francesco del Giocondo, the portrait of Mona Lisa, his wife. Leonardo undertook to paint, for Francesco del Giocondo, the portrait of Mona Lisa, his wife. Who inherited The Mona Lisa when Leonardo died? On his death the painting was inherited, among other works, by his pupil and assistant, Salaì. On his death the painting was inherited, among other works, by his pupil and assistant, Salaì.10 Facts You May Not Have Known about Mona Lisa

Quiz-summary

Information

Results

Average score

Your score

Categories

1. Question

1 points

2. Question

1 points

3. Question

1 points

4. Question

1 points

5. Question

1 points

6. Question

1 points

7. Question

1 points

Mona Lisa gave birth to six children—three boys and three girls—and acquired a stepson from her husband’s first marriage.

Mona Lisa gave birth to six children—three boys and three girls—and acquired a stepson from her husband’s first marriage.

8. Question

1 points

9. Question

1 points

10. Question

1 points

Join the ITALIANO ALLA MANO club for weekly study plans, learning materials and tips: