Written by Janine C. Funk / Scritto da Janine C. Funk

Article edited by Mirella. For simplicity we used passato prossimo instead of passato remoto

The History of Italian Culture / La Storia della Cultura Italiana

Part 1: The Etruscans / Capitolo I: Gli Etruschi

When you think of Italy, you probably think of Rome, the ancient heart of the Classical world and the center of one of history’s most esteemed empires. With 7.3 million international visitors in 2017, the city remains a top tourist destination and cultural landmark. But before the Colosseum and the Forum, before the Pantheon and the Arch of Constantine, when Rome was just a small collection of pastoral settlements whose names have been long lost to history, Italy belonged to the Etruscans.

Quando pensi all’Italia, pensi probabilmente a Roma, il cuore antico del mondo Classico ed il centro di uno degli imperi più stimati della storia. Con 7,3 milioni di turisti internazionali nel 2017, la città rimane una destinazione superlativa e una pietra miliare della cultura. Però, prima del Colosseo e del Foro, prima del Pantheon e del Arco di Constantino, quando Roma era solo un piccolo gruppo di cittadine pastorali i cui nomi si perdono nella storia, l’Italia ha appartenuto agli Etruschi.

The Etruscans were a group of indigenous peoples that inhabited the area of central Italy between the Arno river, which passes through Florence and Pisa, and the Tiber river, which flows through Rome, from at least the eleventh to the first century B.C.E. . Their political and cultural influence, however, reached far beyond the borders of Etruria – today, accounting for parts of Tuscany, Lazio and Umbria – across both space and time. Due to their significant impact on the development of modern Italian culture, including the adoption and adaptation of the Greek alphabet, mythology and art, the Etruscans are considered to be “… the most important of the indigenous peoples of pre-Roman Italy…”

Gli etruschi erano un gruppo di persone indigene che abitavano l’area dell’Italia centrale tra il fiume Arno, che attraversa Firenze e Pisa, e il fiume Tevere, che attraversa Roma, almeno dall’undicesimo secolo al primo secolo a.C. Però, l’influenza politica e culturale degli Etruschi si estendeva lontana oltre i confini di Etruria – oggi, include parte della Toscana, del Lazio e dell’Umbria – attraversando spazio e tempo. A causa del loro significativo impatto sull’evoluzione della cultura Italiana moderna, compresa l’adozione e la modificazione dell’alfabeto, della mitologia e dell’arte dei greci, gli etruschi sono considerati “…la più importante popolazione indigena dell’Italia prima dei romani…”

The Etruscans are particularly famous for their artistic achievements. Beginning in the late eighth century B.C.E., Etruscan art was heavily influenced by their Aegean and Levantine trading partners, which introduced new materials, techniques, and iconography such as “…the human figure, real and fantastic beasts (especially the lion), and vegetal and geometric motifs…” It is during this era, referred to as the Orientalizing period (late 8th – early 6th centuries B.C.E.), that the art forms for which the Etruscans are most celebrated – bronze work, pottery, sculpture, and wall paintings – emerged.

In particolare, gli etruschi sono famosi per le loro realizzazioni artistiche. Iniziando nell’ottavo secolo a.C., l’arte etrusca è stata molto influenzata dai loro compagni di commercio Egei e Levantini, che hanno introdotto nuovi materiali, nuove tecniche, e nuove iconografie come “…la figura umana, le bestie reali e fantastiche (specialmente il leone), e motivi vegetali e geometrici…”. Durante quest’epoca, che si chiama il periodo dell’Orientalizzazione (dalla fine dell’ottavo secolo fino all’inizio del sesto secolo a.C.), sono nate le forme di arte per cui gli Etruschi sono più celebri: la bronzistica, la ceramica, la scultura, e l’imbiancatura.

Thanks to rich local metal deposits, and contact with traders from Greece and the eastern Mediterranean, Etruscan production of bronze goods flourished. Even in antiquity, northern Etruscan cities were well known for their abilities to shape bronze into beautifully engraved hand-held mirrors, which were often decorated with scenes from Greek mythology, and votive statuettes, which were presented as offerings at sanctuaries and other sacred sites. However, it was not until the Classical period (c. 480-300 B.C.E.) that large-scale hollow-cast masterpieces – including perhaps the most famous Etruscan bronze, the Chimera of Arezzo (c. 375-350 B.C.E., Florence, Museum of Archaeology) – appeared. The curious elongated bronze figures of Volterra, including the Evening Shadow (c. 2nd century B.C.E., Volterra, Museo Etrusco Guarnacci), also began appearing during this era; these abstract votives would later inspire the early Italian tradition of board-like statuettes.

Grazie a depositi ricchi di metallo e il contatto con i mercanti della Grecia e del Mediterraneo orientale, la produzione delle merci di bronzo prosperava. In antichità, le città etrusche del nord erano famose per le loro abilità di plasmare bellissimi specchi incisi che ornavano spesso con scene della mitologia greca, e le statuine votive che offrivano ai santuari e ad altri luoghi sacri. Comunque, capolavori più grandi – come il bronzo etrusco più famoso, la Chimera d’Arezzo (c. 375-350 a.C., Firenze, Museo dell’Archaeologia) – non sono apparsi prima del periodo Classico (c. 480-300 a.C.). Durante quest’era, le curiose statuette allungate di Volterra, come l’Ombra della Sera (c. 200 a.C., Volterra, Museo Etrusco Guarnacci), hanno iniziato anche ad apparire; queste votive astratte hanno in seguito ispirato una tradizione italiana delle statuette schiacciate.

Bucchero, or “grey ware”, was developed in Ceveteri, as early as 675 B.C.E., and exported as far as Iberia and the Levant. This pottery was esteemed for its glossy dark grey to black finish, caused by the oxidation of the clay’s reddish ferric oxide while in the kiln. The forms that bucchero took are believed to have been inspired by both Greek pottery styles and contemporary metalwork, especially bronze. In addition to commonplace items like bowls, cups and jugs, bucchero was also shaped into cleverly designed vessels resembling animals, such as the cockerel of Viterbo. Most bucchero vessels were not decorated, but those that were embellished were incised or embossed with simple lines, geometeric patterns, motifs, and scenes from Greek mythology; some bucchero, in imitation of metalwork, were covered with gold or silver leaf, or with a thin layer of tin.

Bucchero si è sviluppato a Ceveteri circa 675 a.C., ed esportato fuori dell’Italia, alla penisola Iberica, al levante, e altre aree dell’Europa. Questa ceramica era pregiata per la sua lucida finitura nera, causata dell’ossidazione del rosso ossido ferrico nell’argilla. Le forme del bucchero s’ispiravano alle ceramice greche e ai metalli contemporanei, specialmente i bronzi. In aggiunta agli articoli usuali come le ciotole, le calici e le caraffe, bucchero veniva plasmato in recipienti ingegnosi che assomigliavano ad animali, come il galletto di Viterbo. La maggior parte del bucchero non è decorato, ma alcuni recipienti sono decorati con solchi semplici, disegni geometrichi, motivi, e scene di mitologia greca. Altri recipienti sono coperti con fogliame d’oro, di argento, o di latta per imitare i metalli.

The Etruscans used sculpture primarily for funerary or religious purposes, including sarcophagi, ash urns and votive offerings made from terracotta, local stone such as alabaster, limestone, sandstone and tufa, and bronze. Beginning in the seventh century B.C.E., large stone and terracotta figures began appearing in tombs as either representations of tomb guardians, like those in the Tomb of Five Chairs in Cerveteri (c. 625-600 B.C.E.), or replacements for the bodies of the deceased, as seen in terracotta and bronze urns in Chiusi. Some painted terracottas, such as the Sarcophagus of the Spouses (c. 525-500 B.C.E., Rome, Villa Giulia Museum), offer some insight into the nature of everyday Etruscan life, as well as funerary rituals. The Sarcophagus of Spouses, which depicts a married couple reclining on a banqueting couch, once brightly coloured, suggests that Etruscan women were regarded with more significance than their Greek counterparts. In addition, the wineskin cushions upon which the couple lounges may be a reference to the sharing of wine, an important aspect of Etruscan funerary ritual; the woman also appears to be pouring something, perhaps perfume, into her husband’s palm, alluding to the offering of perfume, another essential element of the Etruscan funeral.

Gli etruschi usavano principalmente le sculture per scopi funerari o religiosi come i sarcofaghi, le urne e le offerte votive di terracotta, di pietra locale come alabastro, calcare, arenaria e tufo, e bronzo. Dal 700 a.C., grandi figure di pietra e terracotta cominiciavano ad apparire nelle tombe in veste di rappresentazioni dei guardiani delle tombe, come quelle nella Tomba di Cinque Sedie a Cerveteri (c. 625-600 a.C.), o come sostituzioni dei corpi dei defunti, come le urne di terracotta e bronzo a Chiusi. Qualche terracotta dipinta, come il Sarcofago degli Sposi (c. 525-500 a.C., Roma, Museo Villa Giulia), offre alcuni scorci della natura della vita ordinaria degli etruschi, e anche dei riti funerari. Il Sarcofago degli Sposi raffigura una coppia sposata su un divano banchetto, che suggerisce che le donne etrusche avevano maggiore importanza delle donne greche. Inoltre i cuscini [WINESKIN] sono probabilmente un riferimento alla condivisione di vino, che era un aspetto importante dei riti funerare. La donna sembra versare qualcosa, forse profumo, sul palmo della mano del marito; quest’azione allude all’offerta dei profumi, che era un’altra parte essenziale dei funerali etruschi.

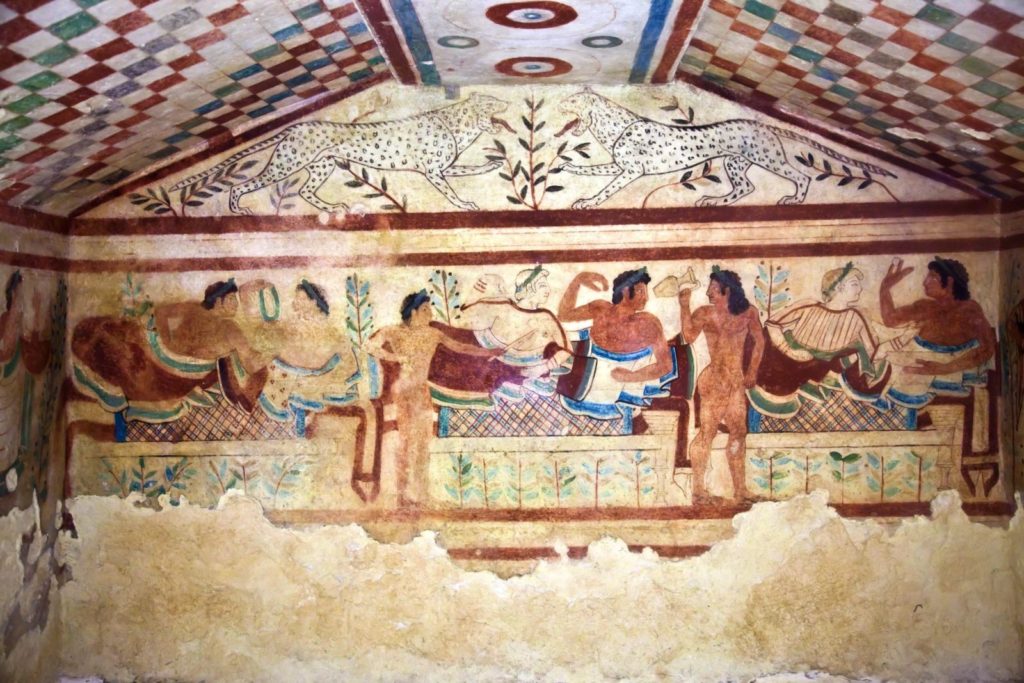

Many of the best examples of Etruscan painting were discovered in cemeteries, or necropoli, such as Monterozzi, near Tarquinia in Lazio, where huge works, depicting scenes of aristocratic life in Etruria, cover the interior walls of rock-cut chamber-tombs. One such tableau, found in the Tomb of the Lionesses in Monterozzi (c. 560 B.C.E.), illustrates a banquet, with dancers and musicians, and finely dressed nobles attended by naked servants. A second Monterozzi tomb painting, found in the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing (c. 510 B.C.E.), depicts a man hunting birds with what appears to be a slingshot, and a boat of fishermen casting a net. The murals of Monterozzi, along with a few other major centers, account for the largest surviving collection of wall paintings in the ancient world, outside of Egypt, Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Molti buoni esempi delle imbiancature etrusche sono state scoperte a necropoli, come Monterozzi vicino a Tarquinia nel Lazi, dove grandi imbiancature coprono le pareti delle tombe e mostrano scene della vita aristocratica in Etruria. Per esempio, un’imbiancatura nella Tomba delle Leonesse a Monterozzi (c. 560 a.C.) raffigura un banchetto con i ballerini, i musicisti, e i servi nudi che assistano gli aristocratichi. Una seconda imbiancatura a Monterozzi, nella Tomba della Caccia e della Pesca (c. 510 a.C.), raffigura un uomo che caccia gli uccelli con una fionda, e una barca con pescatori che gettano una rete. I murali di Monterozzi insieme a pochi altri centri importanti, sono considerati la più grande collezione di delle imbiancature del mondo antico fuori dall’Egitto, di Pompeii, e di Erculano.

When the Romans conquered the Etruscans in the late third century B.C.E., much of their culture disappeared as Etruscan nobles discarded their traditions for those of the dominant Greco-Roman society. However, the Etruscans also had a significant impact on Roman culture, as seen in the Roman adoption of Etruscan art, dress, music, and language. Today, the Etruscans survive in more than just museum collections; they survive in the artistic and cultural developments of their successors, and in the modern language that we know as Italian.

Quando i romani hanno conquistato gli etruschi nell’terzo secolo a.C., la maggior parte della loro cultura è morta, perché gli etruschi aristocratichi hanno abbandonato le loro tradizioni in favore di quelle della società greco-romana. Però, gli etruschi hanno avuto un’impatto significativo sulla cultura dei romani, che hanno adottato l’arte, i costumi, la musica e la lingua degli etruschi. Oggi, gli etruschi sono sopravvissuti non solo nelle collezioni dei musei; ma sono sopravvissuti negli sviluppi artistichi e culturali dei loro successori, e nella lingua moderna che conosciamo come la lingua italiana.

About the author:

Janine studies anthropology and history at university. She has a passion for the culture and the history of Italy, and she likes to share what she learns. He has been studying Italian with Mirella for several years. Some day she hopes to become a curator in a big museum in Europe, perhaps in beautiful Italy.

Janine studia antropologia e storia all’universita’. Ha una passione per la cultura e la storia d’Italia, e le piace condividere quello che impara. Studia l’Italiano con Mirella da parecchi anni. Qualche giorno spera diventare una curatrice in un museo grande in Europa, forse nella bella Italia.

- I massacri delle foibe – Il Giorno del Ricordo

- Estate di San Martino- leggenda e tradizioni

- Michela Murgia: tenace scrittrice e attivista italiana

- I Vini italiani |Storia e Cultura

- Italian Formal and Informal pronouns

- 26 Italian women who made history

- Introduction to the Samnites | I Sanniti – introduzione

- The career of the movie icon, Sophia Loren

- Let’s discover the Tremiti Islands